New Monsters in America

In June, the Treasury Department announced that a woman’s portrait will accompany Alexander Hamilton’s on the redesigned $10 bill that will circulate in 2020. On Sunday, The New York Times called for a woman to appear on the $20 bill. It offered a list of candidates: Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells, Rosa Parks, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Frances Perkins. Conspicuously absent was the only American woman ever to have secured a featured spot on paper currency: Martha Washington.

In June, the Treasury Department announced that a woman’s portrait will accompany Alexander Hamilton’s on the redesigned $10 bill that will circulate in 2020. On Sunday, The New York Times called for a woman to appear on the $20 bill. It offered a list of candidates: Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells, Rosa Parks, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Frances Perkins. Conspicuously absent was the only American woman ever to have secured a featured spot on paper currency: Martha Washington.

The new ten will be the first bill to feature a female portrait since the 19th century, and women’s political participation has changed since then. When Martha Washington appeared on silver dollar certificates printed in 1886, 1891, and 1896, she was the icon of political womanhood. She never voted or held an elected office, yet her portrait occupied a place reserved for prominent political figures. Washington represented a version of political womanhood that dominated American culture: the highest form of female patriotism was indirect political participation, especially to support one’s husband and family.

Within a few decades after her death in 1802, Washington was the most recognizable woman in America. Her portrait circulated widely from the 1830s through the nation’s centennial in 1876. Washington’s image was used to promote an ideal of indirect political participation in direct opposition to the growing woman’s rights movement. Rufus Griswold, a prolific author and editor, placed Washington’s portrait at the front of his 1855 political history of the new nation, The Republican Court. Alongside the details of her husband’s political feats, Griswold lauded Martha Washington for her beauty and skill at hosting her husband’s political gatherings because she never forgot “the requirements of feminine propriety.”

The version of political womanhood that Washington represented became so popular that both the Union and the Confederacy used her portrait to promote their cause during the Civil War. By the time her portrait made it on the silver dollar certificate, Washington’s status as an icon of political womanhood had been part of American culture for decades.

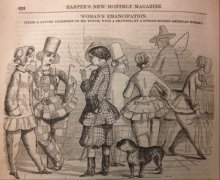

“Women’s Emancipation, ” Harper’s Magazine, 1851 (Boston Athenaeum)

Griswold labeled the reformers who rejected Washington’s model of womanhood “shameless females” and “curious monsters.” He and others argued that if women engaged in politics they would become masculine. A separate visual vocabulary emerged to make the contrast clear. An 1851 engraving from Harper’s Monthly Magazine called “Woman’s Emancipation” lampooned reformers by depicting them in bloomers (rather than dresses) with overcoats disguising their female forms. Instead of caring for children, they leaned on canes and smoked pipes.

бет бум букмекерская контора

You might also like